In the peculiar alchemy of photography, fleeting configurations of light and shadow are transformed into images and objects, capturing a moment, a landscape, a life. In the present moment, when images proliferate and their meanings multiply into an infinity of implications, the experimental photographic works of Michael Koerner and Binh Danh serve as serene documentation of humanity's deep chemical and mythological lineages. From the aqueous origins of our dark past to the electric thread of current consciousness, we grow in our capability to perceive, comprehend, and transform. Koerner's poetic chemical assays and Danh's gleaming testimonial daguerreotypes remind us that we are defined, both physically and philosophically, by values of light and shadow, and that from the shadows of the darkroom, captured light becomes the bright evidence of our existence, humanity, and capability to make and behold beauty. A selection of works by Koerner and Danh will be exhibited at Lisa Sette Gallery along with a single work by Benjamin Timpson, from January 13 to February 24, 2024, with an opening for the artists on Saturday, January 13, 2024 from 1:00 - 3:00pm.

-

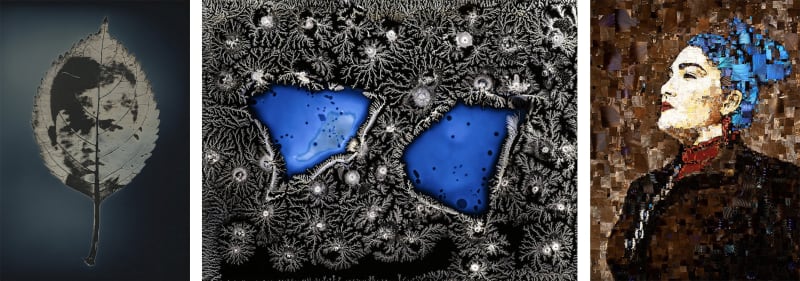

Binh Danh, Untitled #19, from the series, "Aura of Botanical Specimen", 2023

Binh Danh, Untitled #19, from the series, "Aura of Botanical Specimen", 2023 -

Binh Danh, Untitled Bhodi leaf, from the series, "Aura of Botanical Specimen", 2023

Binh Danh, Untitled Bhodi leaf, from the series, "Aura of Botanical Specimen", 2023 -

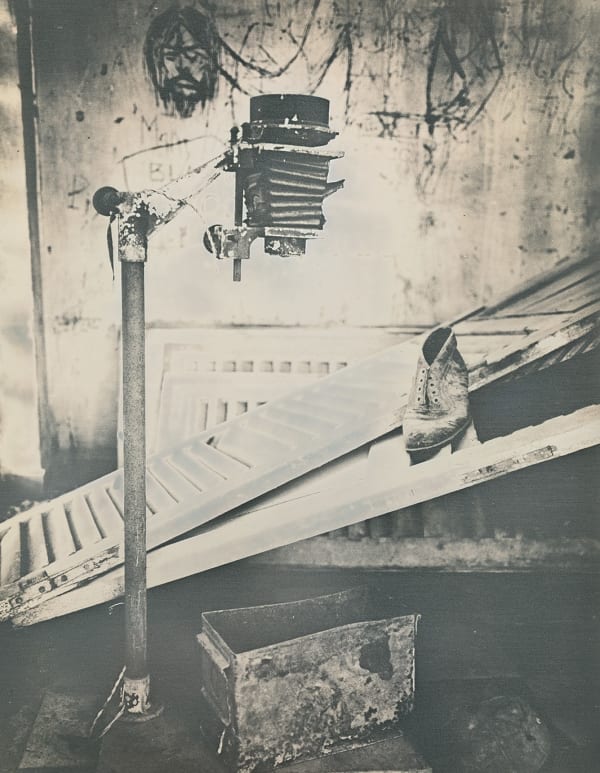

Binh Danh, Photo Enlarger at Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, 2017

Binh Danh, Photo Enlarger at Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, 2017 -

Binh Danh, Lambency of Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum #3, 2017

Binh Danh, Lambency of Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum #3, 2017

-

Binh Danh, Angkor Thom Ruins, 2017

Binh Danh, Angkor Thom Ruins, 2017 -

Binh Danh, Reflection of Angkor Wat Temples, Siem Reap, 2017

Binh Danh, Reflection of Angkor Wat Temples, Siem Reap, 2017 -

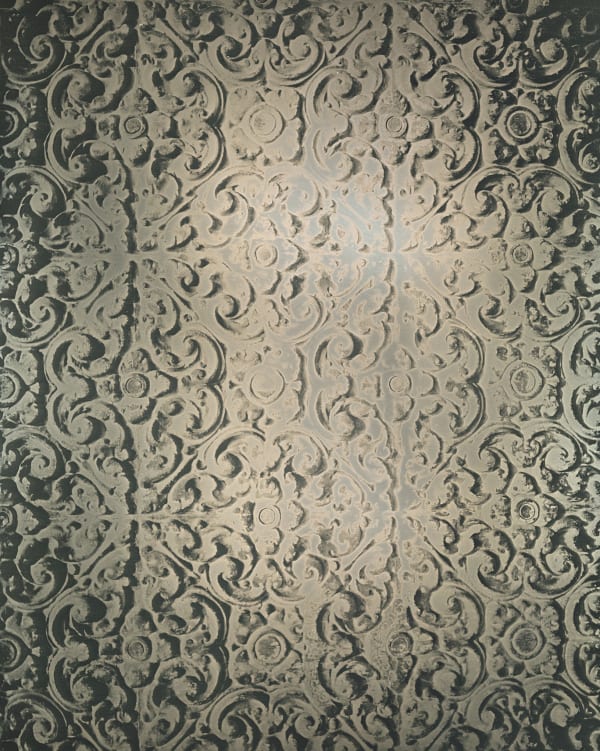

Binh Danh, Angkor Wall, 2017

Binh Danh, Angkor Wall, 2017 -

Binh Danh, Divinities of Angkor Wat #1, 2017

Binh Danh, Divinities of Angkor Wat #1, 2017

-

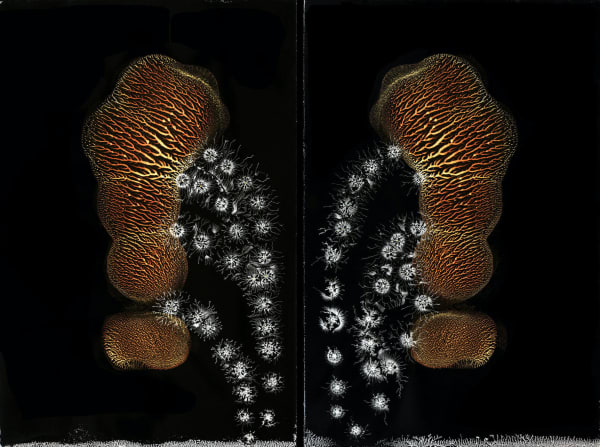

Michael Koerner, Hibakusha Landscape #0404L - #0420R, 2020

Michael Koerner, Hibakusha Landscape #0404L - #0420R, 2020 -

Michael Koerner, Maru #7745, 2018

Michael Koerner, Maru #7745, 2018 -

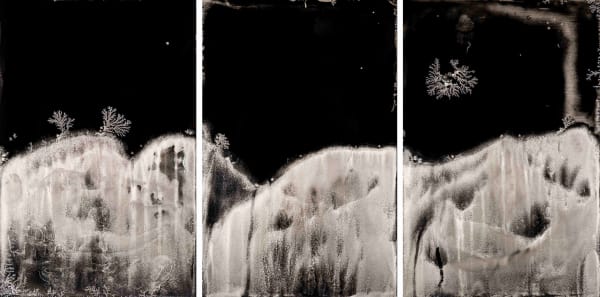

Michael Koerner, Hibakusha Landscape #0416L, #0408C, #0412R, 2020

Michael Koerner, Hibakusha Landscape #0416L, #0408C, #0412R, 2020 -

Michael Koerner, Telos DNA #8781L - #8773R, 2019

Michael Koerner, Telos DNA #8781L - #8773R, 2019

-

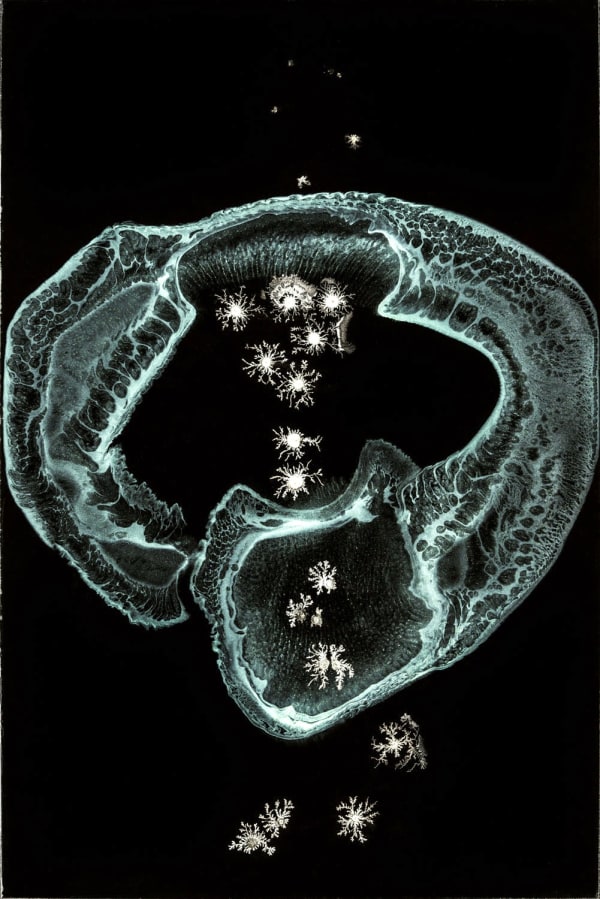

Michael Koerner, Blue DNA #0973, 2021

Michael Koerner, Blue DNA #0973, 2021 -

Michael Koerner, The God Cell #0771L - #0832R, 2020

Michael Koerner, The God Cell #0771L - #0832R, 2020 -

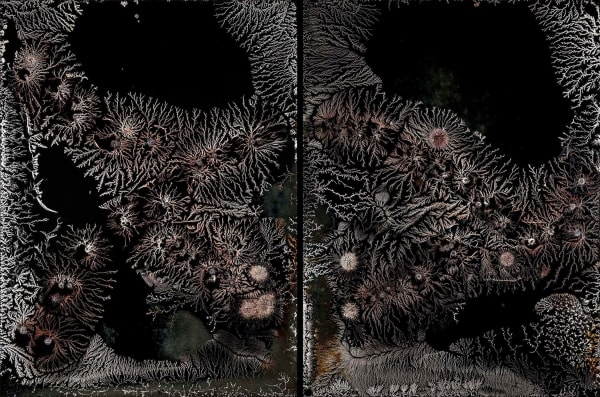

Michael Koerner, The God Cell #0858L - #0854R, 2020

Michael Koerner, The God Cell #0858L - #0854R, 2020 -

Michael Koerner, Blue DNA #1177L-#1181R, 2021

Michael Koerner, Blue DNA #1177L-#1181R, 2021

Shadow Passes, Light Remains

Exhibition Dates:

January 13 - February 24, 2024

Opening Reception with the artists:

Saturday, January 13, 2024

1:00 - 3:00pm

In the peculiar alchemy of photography, fleeting configurations of light and shadow are transformed into images and objects, capturing a moment, a landscape, a life. In the present moment, when images proliferate and their meanings multiply into an infinity of implications, the experimental photographic works of Michael Koerner and Binh Danh serve as serene documentation of humanity's deep chemical and mythological lineages. From the aqueous origins of our dark past to the electric thread of current consciousness, we grow in our capability to perceive, comprehend, and transform. Koerner's poetic chemical assays and Danh's gleaming testimonial daguerreotypes remind us that we are defined, both physically and philosophically, by values of light and shadow, and that from the shadows of the darkroom, captured light becomes the bright evidence of our existence, humanity, and capability to make and behold beauty. A selection of works by Koerner and Danh will be exhibited at Lisa Sette Gallery from January 13 to February 24, 2024, with an opening for the artists on Saturday, January 13, 2024 from 1:00 - 3:00pm.

In processing his fascinating tintype plates, artist and chemist Michael Koerner communicates with his lost family in the darkroom; his mother and her family, who were living in Nagasaki at the time of its bombing; his father, who served on a Navy ship during the Bikini Atoll nuclear experiments; and his siblings who perished due to cancer and other genetic anomalies. The voices and traumas of the past inform Koerner's experiments, illuminating parallels between genetic mutation and the exuberant crystalline fractals that burst unexpectedly from Koerner's timed chemical exposures. Acid and salt solutions on coated metallic plates result in unpredictable chemical transfigurations, resembling blossoms, clouds, or ghostly limbs, reaching across the photographic surface, transforming the narratives of war and loss into stunning repositories of light and form.

Koerner's works can resemble otherworldly landscapes or radiological medical images, as though with the chemical tools of photography the artist has unlocked a subconscious realm, producing windows into the wordless places of loss, yearning, and hope. In these spaces, which are dense with texture and contrast, Koerner tells the story of war's effects through generations. "In the darkroom," says Koerner, "It's all spiritual and emotional. Eventually, suffering must be processed here." However, the drive to make art is an equally insistent and powerful force in Koerner's life, a medium wherein his ancestral cultures, his family's love, and his own scientific and aesthetic examinations result in prolific and profound works. "There's beauty in this damage," Koerner states.

In the ethereal reflective surfaces of Binh Danh's large-scale daguerreotypes, and in the images' paradoxical subject matter, the viewer is invited to explore the issues of self, creativity, and our simultaneous tendency toward destruction. His portraits of the locations and victims of the Khmer Rouge genocide, many exposed on the delicate surface of a leaf, then transferred to daguerreotype, recall the complex arterial nature of exquisite bas-relief scenes on the temples of Angkor Wat, which are also the subject of several of Danh's images.

"With Angkor Wat," says Danh, "here is this beautiful architectural achievement of art and religion and Buddhist culture. And it was through the beauty of the Angkor Wat temple that the Khmer Rouge emerged, as the regime sought above all to return Cambodia to its glory days. In order to do that, they had to remove anyone who did not go along with their ideology. This is a theme I return to: the darkness and beauty in our history."

Danh's poignant, unflinching memorials capture both the moral collapse represented by Tuol Sleng-a former high school turned Khmer prison and execution site-and the sublime deep forests and structures of Angkor Wat. These works invite the viewer to consider how our existence is part of a larger narrative in human history, one that involves both sorrow and transcendence. When you look at the mirror-like surface of a daguerreotype, Danh remarks, "You become part of the image. You are able to reflect yourself onto this landscape."

The intensely silver surfaces of Danh's works often seem to result in a vibration of shadow and light around the subject's edges, as though in the photograph we may finally glimpse the complicated interplay of matter and energy inherent in all life. Whether in the stark chambers of injustice or the luminous expressions of monumental gods, Danh's images record the hidden magic at play in human endeavors. As we contemplate the machinations of human destruction, we are at the same time living in the shadow of the Buddha's form, rising up from the forest floor.

For both Koerner and Danh, processing darkness into light in photographic work is a strategy for bearing witness to the immense mystery of our human existence, bringing forth from the darkness an opportunity to bask in the light of this moment.

In the Atrium:

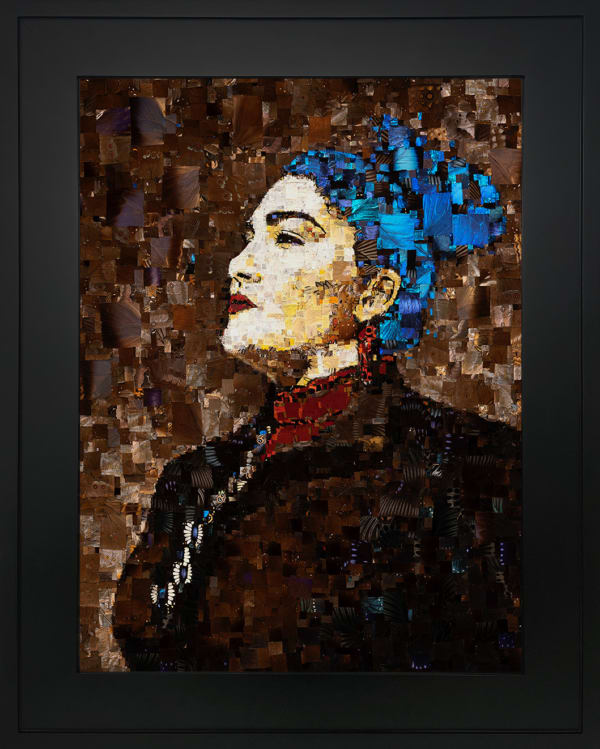

Benjamin Timpson's luminous portraits are constructed of butterfly wings, each visage delineated through mysterious patterns and complex interplay of color and iridescence. The delicate biological relics are responsibly sourced by the artist, deconstructed according to their unique markings, then pieced over the artist's rough sketch on a lightbox.

A descendant of Puebloan peoples, Timpson's transcendent works portray Indigenous women who have been the victim of sexual assault and murder - a population that is four times more likely to experience such violence.

Timpson's newest piece, Melodi, is a composition made fro ma Jeffrey Wolin photograph taken for his Faces of Homelessness series. Melodi, a survivor of sexual assault and domestic violence, is a 5th generation veteran who now works to advocate for specil needs, education, and the Native American community in Chicago, Illinois.

Timpson sees these portraits as a metaphor for the significance of individual lives impacted by cultural violence, and as a way of examining the horrors of centuries-long exploitation of Native lands and cultures. Yet Timpson considers his work an act of hope and catharsis. The artist remarks: "The butterfly is appropriate because there's a metamorphosis that takes place with these portraits; my work is about giving voice to the voiceless, and bringing to light the lives of these women."